[Note: ISL Translation to Follow Soon]

There's a particular type of reaction I've been having this

last year or two, when I post online about some new discovery I've made about

the area of Deaf history I am researching. It's best explained like so: Deaf people

are shocked at what I've found - but at the 'wrong' aspect of it; and I get

peeved. This is not an emotion I am proud of at all, but it has to be

acknowledged - and analysed; and in unpicking this emotion I've been feeling,

it's opened up a lot of stuff for me about the place of the 'outsider' or

comparatively-privileged researcher operating within a minority, oppressed

community that I thought I'd share.

So let's say I find some newspaper story about a Deaf inmate

in the workhouse. Let's call him Billy McEvoy. Billy McEvoy is a long term

resident in the workhouse, as were many Deaf people in the period I focus on,

and Deaf paupers are generally portrayed as lacking agency or capacity for

resistance. But in this news story I find, Billy writes a long, well written

and coherent letter of complaint to the workhouse Guardians. The letter is

reproduced in full in the paper, and details in heart-rending fashion his

version of the mistreatment at the hands of the authorities. Elements in

Billy's letter speak of his missing other Deaf people’s company; a feeling of

being victimised because he is Deaf; his application, say, for a position in

the workhouse staff that he feels he is owed. There might be several other

nuggets of detail illuminating aspects of life for poor Deaf people in the

nineteenth century. Horrific experiences of marginalisation, and the dismissive

- often callous - disregard for them as human beings by workhouse guardians.

But also, resistance to hearing oppression and pride in their language and

community. And not least, further proof that Irish Deaf people's written

English during the nineteenth century was excellent.

And I light up! I excitedly throw up the article on Twitter

and Facebook, hoping that a Deaf audience will see the same significance to

this as I do - that same feeling of joy (mixed with sadness, of course) in

discovering the previously unknown. But here's the issue: many, even most, of

the replies from Deaf people on social media don't focus on any of this at all.

Instead, they express their horror and sadness at... the use of the phrases

'deaf and dumb' and 'deaf mute', or even 'dummy' in the newspaper article. And

that's all. This frustrates me. And it shouldn't, of course; I'm ashamed of the

reaction, for many reasons.

I'm an outsider researcher,[1] a hearing person privileged to

be able to explore the lived experiences and histories of a minority community.

And though my work may help to illuminate issues of concern to Deaf people and

coincide with their agendas, it is still, at the very least, unfair of me to

set any agenda in terms of what aspects of my research should be perceived as

more salient or important than others. It's not up to me how the Deaf community

receives my work. How the work is received, in fact, should probably inform its

direction.

But there's also this: after five years of looking at reams

of nineteenth century documentation about Deaf people in Ireland, I’ve seen the

phrases ‘deaf and dumb’, ‘deaf mute’ and the dreaded ‘dummy’ (hereafter written

‘d___y’) so often, that I have almost entirely lost that punch-in-the-stomach

reaction to them that I get when I see them used in, say, a modern tabloid

story. I'm at such a knee-deep stage of research that the use of these awful,

outdated, and currently offensive, terms for Deaf people washes over me. I

might occasionally wince at some headline using the above phrases; I smirk over

some badly-written Victorian 'deaf humour' written by copy editors to stick in

a spare half-inch of column, jokes that use language in a way that

retrospectively lampoon the authors more so than Deaf people.

|

| Case in point. |

But I have lost - or perhaps more accurately, never really

possessed - something visceral and deeply connected to identity and being, that

reacted when I heard these phrases. I've been involved in the Irish Deaf

community for nearly 20 years now as a researcher and interpreter, and so I can

afford, in some sense, to have post-modern, detached conversations and musings

about labels such as 'deaf and dumb' and 'deaf mute'; to wonder if maybe

medical-model equivalents such as 'hearing impaired' are far worse, in some

way, portraying people as intrinsically broken; to despair at hearing people

who stutter and splutter and hem and haw when trying to describe a person's

'condition', when right-thinking people just say 'Deaf'. You could point out

that Deaf people described themselves as deaf and dumb years ago (even if it

appeared they had a preference for 'deaf mute'[2]). You can even excuse the

older hearing members of your family who will still talk about the village

'd___y' of their childhood, because, well, they are old, they mean well, they

don't really mean it in a prejudiced way.

But of course, I can afford to become inured to this

terminology - because of my hearing privilege; because it's not about me. I

will never have that instinctive hurt, that wound, that feeling I cannot even

dare to try and guess at describing, that comes from being called something so

dismissive. I'm especially thinking of ‘d___y’ and thinking in terms of

equivalence with what I’ll call the ‘N word’ - used, despicably, to describe

African Americans. I’m not saying it’s ‘the same’, but there are some

ramifications to this line of thought that lead me to a comparison where my own

reactions to words are concerned. Because what is my own personal reaction to

seeing these terms used so consistently, so often?

My reaction to the ‘D-word’ puts me in mind of the movie

Blazing Saddles, still a favourite of mine, where the 'N-word' seems deployed

self-consciously, as a way to ridicule its users; the rednecks who drawl the

word are painted as buffoons, and the racism on display is made to look as

ridiculous as racism is, the use of the N-word being a hallmark of that idiocy.

Similarly, I see nineteenth-century headlines with 'd___y' used in all

seriousness, in headlines such as 'A D___y In Trouble', 'Sympathy for the

D___y', etc. – and I have lost the reaction of rage; instead, confronted with

these words in their historical context time and time again, this ridiculous

bigotry, I snicker. It seems a cartoonish buffoonery in print, a jocular

example of how awful the past was (and by implication how much better it is

today); and eventually, I can get to the stage I don't even register the word

when I enter d___y into a newspaper search archive, or note down that our

friend Billy McEvoy is marked down in the workhouse register as being a d___y.

But this is not the reaction of Deaf people, who do not have

the luxury of comforting themselves that ‘this is all in the past’. This is not

a ‘past’ that has disappeared. The D___y word still has currency. ‘Deaf and

dumb’ still has currency. Terms that have become, for me, a familiar - and

eventually, unremarkable - feature of the historical territory, something to

chuckle off, something to historicise, remain for millions of Deaf people

viscerally hurtful words, an abnegation of their humanity, labels that can

traumatise and re-traumatise. I do not want to shrug off or become immune to

these terms. And I need to realise why this is crucial.

______________

All this puts me in mind of recent controversies that connect

to these considerations of language, and my ‘outsider’ status. I have always

been aware of the profound unhappiness of much of the stories I have stumbled

upon. If you exclude the positivity and community that has been found – and is

still found – by Deaf people in residential schools in Ireland, each kind of

institution I look at in my dissertation is a place where no-one wants to be.

More often than not, there is compulsion – directly in the case of courts and

prisons, as well as mental institutions; indirectly in the case of workhouses.

Deaf people ended up there due to a series of cataclysms, marginalisation,

missed opportunities and mistreatment. Many times, these stories end after

years behind walls, still in these institutions, buried in featureless

makeshift graveyards.

But if I am proposing – as I think I must – that these

experiences were to some degree, unique to Deaf people – uniquely Deaf

experiences of pain and suffering – what does that make me? How can I justify

or explain my role in their documenting? A grandiose part of me feels a

responsibility to ‘uncover’ and ‘share’ these stories. An emancipatory and

reflective historiographical approach would seem to require that I acknowledge

my self in the process. And not that I’m an unconditional fan of their work,

but postmodern historians might insist that in constructing these narratives

based in historical sources, that I am in some sense constructing, not a

scientifically ‘neutral’ and ‘impartial’ account of events, but something more

akin to an intensely personal work of art.[3]

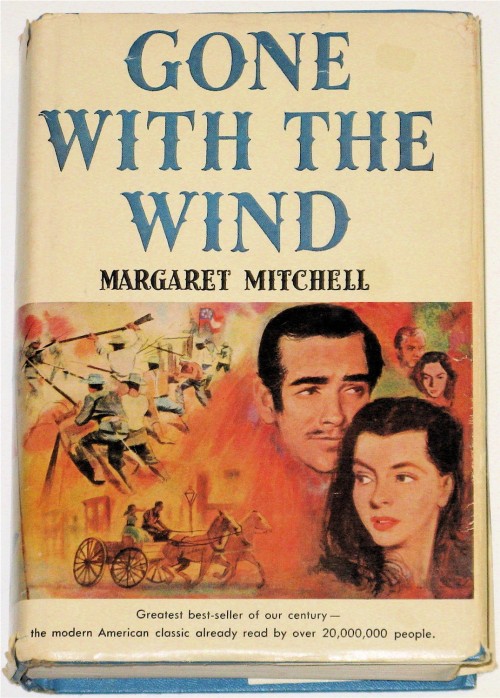

With these in mind, I want to look at two recent enough news

stories around the idea of 'cultural appropriation' that have caused me to

think about the nature of my work, given my outsider status. Firstly, the

Vanessa Place controversy. Place is a conceptual artist based in Los Angeles,

who hit the headlines in 2015 when she opened a Twitter account that aimed to

tweet, line by line, every word of Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel Gone with the

Wind. The aim behind this was provocatively stir up discussion of the racist

heritage of the United States, the legacy of the book and movie in relation to

racist caricature and language, and explore the nature of ‘clicktivism’ and

social media in relation to discussion of arguments around these issues. But

Place is a white, queer female, and her project generated vociferous criticism

from African-American activists infuriated at her apparent recycling of racist

language and imagery, regardless of purpose. In the subsequent Twitter-based

furore, activist groups demanded that Place’s work be boycotted, that she be

disinvited from conferences and removed from academic panels.[4]

Place’s project raises questions about the artistic use of

imagery and language that is considered unacceptable and deeply offensive to

people of colour regardless of ‘benign’ intent. Some of Place’s critics asked

whether “these works successfully perform an anti-racist critique, or do they

unnecessarily retraumatize people of color (and black Americans in particular)

for sensationalist purposes?” Critic Lillian-Yvonne Bertram describes Place’s

piece acting in a “nonchalant” way, which “implies carelessness, a lack of

sincerity when confronted with thoroughly traumatic material”. The project

raised “any number of questions about the ethics of engaging with traumatic

materials at what seems to be little or no risk to oneself”, and Kim Calder

wonders if these

engagements with black trauma raise the question of whether a person who does not ‘own’ a trauma, so to speak, has any right to engage it, despite, or because of, their historical responsibility for that trauma… How could someone who doesn’t authentically know an experience have something to say to those who have an embodied sense of that experience? In addition, if a work is to commit the sin of representing a trauma that is not one’s own, which might cause pain to readers whose direct experience it is — does such work not have a responsibility to tell us something new, or make a difference in the world somehow? [5]

Of a similar vein, but dealing with perhaps more traumatic

content, is the painting of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black youth lynched in

1955. Till’s mother had urged that her son’s body be displayed in an open

casket at his funeral to ‘let the people see’, the resultant fury helping to

spark the Civil Rights movement among black Americans. After listening to tapes

of Till’s mother, white female artist Dana Schutz created a piece of art depicting

Till in his open casket. “‘I don’t know what it is like to be black in America,

but I do know what it is like to be a mother,’ she said, explaining her desire

to engage with the loss of Emmett Till's mother. ‘In her sorrow and rage,’ she

wrote, ‘she wanted her son’s death not just to be her pain but America’s

pain.’”[6]

But the artwork met with a fiercely negative and outraged

reaction from sections of the African-American community. A petition was begun

to not only have the work removed from the Whitney Museum, but destroyed;

“Detractors argued that a white woman ought not render such a subject...

protester Hannah Black, a black artist from Britain, [argued] that a white

artist has no right to paint a lynching victim.” Jonathan Blanks of the Cato Institute’

Project on Criminal Justice felt that “[a]s far as artists are concerned ...

risk is inherent to what they do...

Slavery is America's Original Sin, and the racism that evolved to

perpetuate it is an inextricable part of our social fabric. Whenever any artist

tries to confront that, they inherently invite expressions of the often

chaotic, almost inarticulable pain that exists as a part of black experience in

America.”

So here I stand, a member of the hearing majority, with our

own Original Sins against Deaf people. - oralism, language deprivation,

institutionalisation, disempowerment. Can I afford for a second to be

'nonchalant' with words and language that can still cause such pain?

______________

How to relate this, then, to my writing of experiences that

are not mine, that are so traumatic and so particularly Deaf, as I have myself

defined them? What are the boundaries and considerations I need to have? Or

should I walk away?

It isn’t a new consideration for me. Shortly after I began as

a registered PhD student, I made a decision to restrict the scope of the

dissertation to pre-1924. Prior to thia, I had in mind a grand historical tour

between 1800 and the 1950s, going right the way up to the changeover to oralism

in Cabra. But that changed for a number of reasons. First, and probably

foremost, was the sheer workload that would be involved in covering both

British-administered and Free State Ireland in the one work.

I also had concerns about methodology – as well as some

of the things I’ve mentioned above. It made no sense to write about 1950s Irish

Deaf people without interviewing people, using an ‘oral’ history approach –

which when applied to elderly Irish Deaf people, especially Deaf women, throws

up all kinds of considerations in terms of procedures, language,

confidentiality and trust. And there would be the huge responsibility of

portraying the potentially traumatic, non-shared (with me) lived experiences of

people that were still alive, and able to be potentially deeply hurt by my treatment

of their stories. Which is not to say that after restricting my period to

1816-1924, that I just say, ‘everyone I research about is dead, so it’s grand’.

Methodologically, and ethically, yes, it gets easier to deal with the issues.

But there remains a very strong feeling that I need to do the memories of these

individuals – this community, or communities – justice.

It’s easy, at a surface level at least, to counter the

assertion that ‘hearing people should not write about Deaf historical trauma’ by

offering the observation that historiography is not art, like that of Place and

Schutz, but a form of quasi-scientific inquiry; relying on facts supplied by

critically evaluated sources. However, the position of ‘history as science’ has

taken a pounding by postmodernists, who insist on the impossibility of

objectivity in history writing, and the historiographical text as a literary

construction - a text - and so in ways as amenable to analysis as a form of art

as any painting or poem.[7]

Another argument of mine might point to the profusion of

hearing authors who have written, and continue to write, about the suffering

and oppression of Deaf people at the hands of hearing society – and are lauded

by the Deaf community for having done so: Harlan Lane, for example, wrote When

the Mind Hears, still a core text for Deaf history,[8] which details the

injustice and oppression towards Deaf people in the switch to oralism in

America and elsewhere. Lane is hearing, and still to this day is not a fluent

signer. Owen Wrigley, who grumbles about Lane’s work as representing a form of

‘hearing Deaf history’ that focuses more on hearing ‘benefactors’ than Deaf

people themselves, is himself a hearing

historian.[9] Closer to home, Edward J Crean’s passionate and polemical work

Breaking the Silence was one of the first books in Ireland of its kind to

document the linguistic abuses experienced by Deaf children in the Cabra

schools from the 1940s onwards – writing unashamedly and proudly as a hearing

parent of a Deaf child, who did not sign.[10]

The world is certainly a better one because of the work of Lane,

Wrigley, Crean, and others. The involvement of hearing historians in

documenting the darker aspects of Deaf history continues today. Gunther List

feels that hearing people have a kind of duty to do Deaf history that lays bare

past structural inequalities and oppression of Deaf people. He states that Deaf

historians should not be expected to shoulder the “burden of presenting,

entirely from their own resources, historical record of negative interaction

between majority and minority… minority historians should not have to provide

the necessary revision of the history of the majority”. List conceptualises his

interest as an outsider to Deaf culture as a “focus on deaf people’s historical

conflicts with that group to which I myself belong”.[11] List’s formulation is

one that I agree with and utilise.

There is a third counterpoint: the fact that to date my own

research has been met with near-universal welcome from Irish Deaf people

themselves. I have presented often, almost always in ISL, and from a local or regional

Deaf perspective whenever I could. I’ve been requested to present at Deaf clubs

and events on the strength of word of mouth/hand. That’s not to say there may

not be some disquiet; I’ve talked previously about the danger of becoming theeverblogger, drowning out the quiet, consistent work of Deaf historians with

constant social media barrages, increasing ‘presence’ at the expense of the

true experts in Deaf history - community insiders with a rich pedigree of

research experience. I am keenly attuned to suggestions that I may be

‘colonising’, and am thankful that no such accusations have come toward me as

yet – but aware that indeed they may. I keep in touch with Deaf Irish

historians and offer support and collaboration where it is wanted, and above

all, notify people about sources.

Here is another counterpoint that is weaker, but deserves

discussion: that the traumas I research and describe arise from old patterns of

Irish institutional behaviour and practice, which have become extinct as the

institutions have shuttered, and represent a Deaf experience that is in some

way ‘over’ – and by implication, perhaps more ‘safe’ to discuss and analyse.

But is this really the case? It is true that in Ireland today, no Deaf child is

placed in a forbidding concrete residential institution, returning to their

families twice a year only, and educated purely through signed language;[12]

nobody Deaf or hearing goes to a workhouse or poorhouse; courts provide

interpreters, as do prisons in Ireland;[13] Deaf inpatient numbers in

residential mental health care facilities seem to be dropping, and Deaf

psychiatric care is improving, with a recognition that Deaf people have

specific language needs within the healthcare system.[14]

But to insist that the horrors of the past have passed for

deaf people obscures the fact that this history is not history. Deaf people are

often still poor and unemployed;[15] are still chronically underserved by the

justice and mental health systems, and cannot expect to have an appropriately skilled professional

interpreter in the courtroom or therapist’s office as a matter of course.[16]

Given the injustice that persists – institutionalised injustice, if not exactly

occurring within bricks-and-mortar institutions - it would be incredibly

inappropriate for me to encourage Deaf people, even indirectly, to ‘look on the

bright side – things were worse 100 years ago’.

None of these counterpoints is on unassailable ground, and my

thinking process and action needs to constantly be reviewed in light of all the

above. I do not see myself walking away from the project, and in all of my

honesty, I think it would be the Deaf community’s loss if I did. It may be true

that the individuals I research may be discovered and written about by other

historians – I positively plead for it to happen – but I feel that in my work,

I can bring a perspective that is new, that is my own, that is also of benefit

to the Deaf community in its current struggles against oppression. There is

some vanity in that, but also many examples I can refer to, to back it up. The

research is still mine, the process mine; and while I intend that

non-possessively, I cannot not own and not embed myself in what I am doing.

My dissertation, along with any papers, vlogs or blogs that

come from my PhD research, are always going to be creatures of fierce

contradiction: intensely personal reflections on, and treatments of, some of

the darkest and most painful moments and suppressed memories of the Irish Deaf

community, moments and memories that will resonate viscerally with Deaf people

- in a way they will not, with myself. Therefore it is not - cannot be - an

unthinking process of finding, documenting, disseminating. The subject matter deserves

more humility, consideration and

reflection than describing myself as someone who ‘brings these stories to

light’; I have no wish to display any purloined Elgin marbles in a ‘dark

tourism’ museum of my own making, especially if they speak directly to the

trauma of those who have suffered, as a class, as a culture, as a community -

and continue to suffer. The journey continues.

Some minor edits and corrections made, 4 April, 10.10pm GMT.

_____________________________________________________

[1] Gill Harold makes good use of this term and explores its implications:

Gill Harold, ‘Deafness, Difference and the City: Geographies of Urban

Difference and the Right to the Deaf City’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, National

University of Ireland, Cork, 2012), passim.

[2] Graham O’Shea, ‘A History of Deaf in Cork: Perspectives

on Education, Language, Religion and Community’ (Unpublished M.Phil. Thesis,

University College Cork, 2010).

[3] See Peter Brickley, ‘Postmodernism and The Nature of

History’, International Journal of Historical Learning Teaching and Research 1,

no. 2 (1999) for a discussion of the debates between such writers as Evans,

Hayden White, Keith Jenkins etc. on these points.

[4] Edward Helmore, ‘Gone With the Wind Tweeter Says She Is

Being Shunned by US Arts Institutions’, The Guardian, June 25, 2015; available

from

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/jun/25/gone-with-the-wind-tweeter-shunned-arts-institutions-vanessa-place;

Kim Calder, ‘The Denunciation of Vanessa Place’, Los Angeles Review of Books,

June 14, 2015; available from https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-denunciation-of-vanessa-place/.

[5] Calder, ‘The Denunciation of Vanessa Place’.

[6] Conor Friedersdorf, ‘What Does “Cultural Appropriation”

Actually Mean ?’, The Atlantic, April 3, 2017; available from

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/04/cultural-appropriation/521634/.

[7] See Hayden V White, ‘The Burden of History’, History and

Theory 5, no. 2 (1966): 111–34; Perez Zagorin, ‘History, the Referent, and

Narrative: Reflections on Postmodernism Now’, History and Theory 38, no. 1

(February 1999): 1–24.

[8] Harlan Lane, When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf

(New York, 1989).

[9] Owen Wrigley, The Politics of Deafness (Washington, D.C.,

1996); Wrigley declares that“[p]ainting psychohistories of great men struggling

to attain a place in the history of hearing civilizations has little or nothing

to do with portraying the historical circumstances of Deaf people living on the

margins of those hearing societies.”

[10] Edward J Crean, Breaking the Silence: The Education of

the Deaf in Ireland 1816-1996 (Dublin, 1997).

[11] Günther List, ‘Deaf History: A Suppressed Part of

General History’, in Deaf History Unveiled: Interpretations from the New

Scholarship, ed. John Vickrey Van Cleve (Washington, D.C., 1993), 116.

[12] Marc Marschark and Patricia E Spencer, Evidence of Best

Practice Models and Outcomes in the Education of Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing

Children: An International Review, National Council for Special Education

(Trim, Co Meath, 2009); available from http://www.nabmse.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/07/1_NCSE_Deaf.pdf;

accessed 2 August 2014.

[13] John Lawrence, ‘Irish Jails Home to Prisoners of 66

Nationalities’, Irish Times, December 5, 2016; available from

http://www.irishtimes.com/news/crime-and-law/irish-jails-home-to-prisoners-of-66-nationalities-1.2892735;

accessed 4 April 2017.

[14] Brendan Kelly, Hearing Voices: The History of Psychiatry

in Ireland (Dublin, 2016). Despite the title, this is a general history of

psychiatry in Ireland, but does cover recent developments for services for Deaf

people over four pages.

[15] John Bosco Conama, Carmel Grehan, and Irish Deaf

Society, Is There Poverty in the Deaf Community?: Report on the Interviews of

Randomly Selected Members of the Deaf Community in Dublin to Determine the

Extent of Poverty Within the Community (Dublin, 2002); Pauline Conroy, Signing

In, Signing Out: The Education and Employment Experiences of Deaf Adults in

Ireland (Dublin, 2006).