26 January 2023

123 Years Ago Today... Dungarvan: a Deaf Repeat Offender - and a victim of Police Brutality?

21 January 2023

113 Years Ago... a Deaf Kerry Labourer dies; his will triggers a court battle over a small fortune

- 1901 Census, Laghtacallow - Census of Ireland 1901 online

- 1907 civil death record, Cornelius Corcoran - IrishGenealogy.com

- Google Maps

- 1910 Will Calendar, Cornelius Corcoran - http://www.willcalendars.nationalarchives.ie/

- 1880 Milltown Petty Sessions Order Books, 8 Nov 1880 - FindMyPast.ie

- The Kerryman, 22 May 1909

- Irish Independent, 19 Jan 1910

- Freemans Journal, 19 Jan 1910

- Dublin Daily Express, 19 Jan 1910

- Larne Times, 20 Jan 1910

- Irish Times, 22 Jan 1910

- Killarney Echo, 29 Jan 1910

16 January 2023

114 Years Ago... a Deaf woman brought to court by the workhouse master for assault

|

| Source: Dundalk Democrat, 16 January 1909 |

Some workhouses at certain times had more than one Deaf inmate. Anne McEneaney was a Deaf inmate in Carrickmacross workhouse - but she wasn't the only one.

In 1909 a hearing woman, Bridget Finegan, who was living in Carrickmacross Union workhouse, brought Anne to the local Petty Sessions and accused her of throwing something at her head in the workhouse.

In court, one of the court staff wrote the evidence down for Anne. Anne replied "in a good hand" and cross-questioned Bridget; Anne had her own complaints - being 'interfered with' in the kitchen by Bridget and having milk stolen from her. The workhouse master was then examined; he felt that Anne was 'excitable' - because she was Deaf.

The official Petty Sessions order book states that the charge was proved, but the court felt that "having regard to the mental condition of defendant it is inexpedient to inflict any punishment" and dismissed the charge.

| |

| Carrickmacross Petty Sessions Order Book, 1909; source: www.findmypast.ie |

Interestingly, Anne was declared by the workhouse master to be "not so bad as the dummy already committed to prison" in that same court recently. Who was the other Deaf person? Annie Eakins, who, the previous month, had been sentenced to three months imprisonment in Armagh gaol for assault and breaking glass in the workhouse. Both women were ex-pupils of St Mary's in Cabra - Anne McEnaney entered in 1881, and Annie Eakins in 1889.

Carrickmacross Workhouse is one of the few in Ireland that not only still stands but has been converted to a historic centre.

12 January 2023

Hennessy's School in Cork - Deaf Children in a 'Mainstream' School?

04 January 2023

January 2023: Update!

15 December 2022

I've passed my PhD Viva with minor corrections!

07 December 2022

130 Years Ago ... A Longford Deaf Man, Charged with Murdering his Mother - and Committed to an Asylum

|

A

summary description of the death of Catherine Kean by the Royal Irish

Constabulary. Source: Outrage Reports, 1892, National Archives of

Ireland. |

|

Sligo Jail. Source: https://www.sligogaol.ie/general |

|

John Kean in the Sligo Prison records in 1892. Source: www.FindMyPast.ie |

|

Source: Irish Independent, 2 December 1892, p. 6 |

|

Source: Irish Times, 10 December 1892 |

|

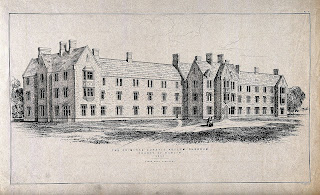

| A drawing of the Dundrum Criminal Lunatic Asylum. Source: https://www.crimeinmind.co.uk/ctshowcase-team-member/1845-dundrum-hospital/ |

|

An anonymised mention of John Kean in the 42nd Report of Inspectors of Lunatics (Ireland) in 1893. |

|

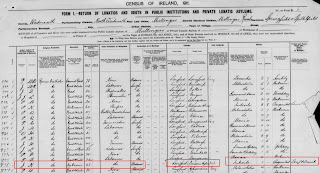

| John Kean in the 1901 Census of Ireland, in the Dundrum Criminal Lunatic Asylum. (Line 70) |

|

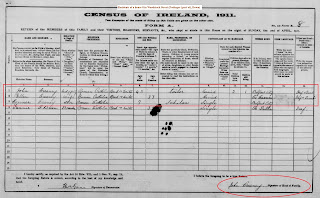

| John Kean in the 1911 Census of Ireland - Mullingar Lunatic Asylum. (Line 826) Please note - John was never married - the description of 'widower' is inaccurate. |

|

| John's death certificate, 1915. Source: https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/images/deaths_returns/deaths_1915/05272/4463466.pdf |

03 December 2022

120 Years Ago ... A Tragic Accident: the Death of a Child of Belfast Deaf Parents

Warning: this post may be upsetting to read for some people.

John

Creaney and Mary Ellen (or just Ellen) Connell were a Belfast Deaf

couple who had married in 1901. Both had attended the Cabra schools. Ellen was originally from Co. Cavan, and in 1901, lived on Brougham St;

she worked as a smoother in a laundry.

Census of Ireland 1901: Brougham St, Belfast. Source: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Antrim/Duncairn_Ward/Brougham_Street/957010/

John

worked as a tailor, and in 1901 lived in an interesting household on

Lisbon St. The head of the house was Sarah Jane Park Ervine, mother of

future Belfast playwright John Greer Ervine. John Creaney was one of

four Deaf boarders with the Ervines at Lisbon St, and the house

contained Deaf members of the Church of Ireland, Catholics and a

Presbyterian. Kate McGoldrick, a Deaf Catholic woman also boarding with

the Ervines in 1901, was a witness at their 1901 wedding. (John had

been married twice before, but his previous wives had passed away.)

Census of Ireland 1901: Lisbon St, Belfast. Source:http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Down/Pottinger/Lisbon_Street/1214931/

When

they married they ended up living at 12 Well Street, and in October of

1902 Ellen gave birth to a daughter, Honoria, born in their home. But

tragedy struck when Honoria was six weeks old - the child died, and an

inquest was held to find out what had happened.

1902 civil birth and death records for Honoria Creany. Source: www.irishgenealogy.ie

The

inquest used the services of an interpreter named J. Stewart. Stewart

would have used Northern Irish variant of BSL, but John and Ellen may

have been familiar with BSL from living with Protestant boarders and

socialising in the Belfast Deaf community. (John and Ellen were listed

since at least 1914 as Catholic "Members and Adherents of the Mission

Hall" in Belfast for Deaf adults, the members being mostly Church of

Ireland and Presbyterian, but a substantial minority of Catholics.) Also

present was the Superintendent of the Belfast Deaf Mission - Francis

Maginn. He may have present as an emotional support to the Creaneys in

this most distressing time, or even acted as a Deaf interpreter, working

between Stewart's BSL to Irish Sign Language

|

| Census of Ireland 1901: Brougham St, Belfast. Source: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Antrim/Duncairn_Ward/Brougham_Street/957010/ |

|

| Census of Ireland 1901: Lisbon St, Belfast. Source:http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Down/Pottinger/Lisbon_Street/1214931/ |

|

| 1902 civil birth and death records for Honoria Creany. Source: www.irishgenealogy.ie |

|

| Source: Mission Hall for the Adult Deaf and Dumb Report, 1924. |

|

| Census of Ireland 1911: Woodstock St, Belfast. Source: http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1911/Down/Pottinger__part_of_/Woodstock_Street/219655/ |

29 November 2022

109 Years Ago: a Deaf Workhouse Inmate complains about her treatment

|

| The workhouse building in Carrickmacross where Anna Eakins spent several years. Source: https://brenspeedie.blogspot.com/2013/08/from-land-wars-to-civil-war-brief.html |

In 1913 in Carrickmacross Workhouse, disagreements between some female inmates led to the Board of Guardians seeking to bring one of them to court - as it happened, a Deaf inmate: Anna Eakins.

|

| Source: Petty Sessions Order Books, Carrickmacross Petty Sessions, 1913. www.findmypast.ie |

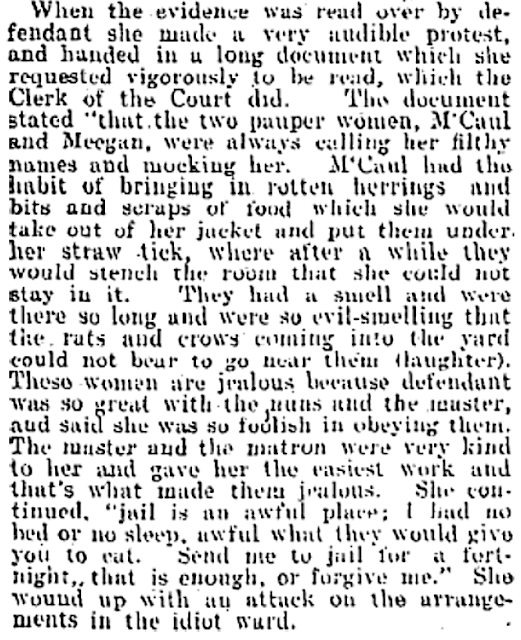

Ellen McCaul (hearing) accused Anna Eakins (Deaf) of assault - threatening her with a sweeping brush, and later, throwing a chamber pot's contents over her. Another hearing woman named Meegan made similar complaints. But there was another side to the story, and we get a glimpse of it through a long letter that Anna wrote for the court which was read out.

|

| Source: Dundalk Democrat, 29 November 1913, p. 14 |

Anna complained that McCaul and Meegan called her names and mocked her, but it was from jealousy that Anna had a good relationship with the workhouse Master and the nuns that worked in the workhouse hospital, and was given manageable work by them. In particular, Anna was scathing about McCaul; she apparently was in the habit of bringing scraps of food into the workhouse (including rotten fish) and hiding them under her mattress, causing a horrible smell in the dormitory where they all slept, which was "so evil-smelling that the rats and crows coming into the yard could not bear to go near them". Anna was afraid to go to prison, and stated that "jail is an awful place"; when she had been there before she "had no bed or no sleep, awful what they would give you to eat". Nevertheless she was resigned to her fate: "Send me to jail for a fortnight, that is enough, or forgive me."

|

| Source: Dundalk Democrat, 29 November 1913, p. 14 |

The case was adjourned for three months and Anna was warned to be on good behaviour.

28 November 2022

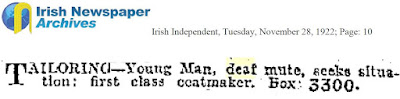

Deaf People Seeking Jobs in 1885 and 1922

26 January 2022

The Generosity of Two Deaf Wexford Men

|

Painting

is called "Heinrich XVII, Prince Reuß, on the side of the 5th Squadron I

Guards Dragoon Regiment at Mars-la-Tour, 16 August 1870" by Emil

Hünten, 1902. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Mars-la-Tour |

In 1870, Prussia and France went to war. The Franco-Prussian war was one of the moves towards a unified German Empire. But the world was shocked at some of the cruel behaviour of the Prussian troops in France. Collections were made around Ireland to assist the injured French troops.

|

| Source: Wexford People 24 September 1870, p. 7 |

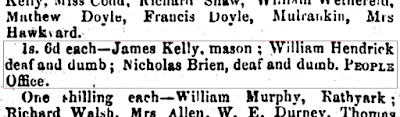

Among those who contributed in Wexford - two Deaf men, William Hendrick and Nicholas Brien. They each contributed 1 shilling 6 pence. William had entered the Prospect School in Glasnevin in 1854. Nicholas entered St Joseph's in 1864.

|

| Source: Wexford People 24 September 1870, p. 7 |

23 January 2022

Old Lisnaskea Workhouse - Reluctant to Send the Deaf Children to be Educated?

The old Lisnaskea Workhouse, Co. Fermanagh. It is now mostly derelict and surrounded by the Lakeview housing estate.

|

| Lisnaskea workhouse - old entrance block |

Not many deaf children were sent to Cabra from Lisnaskea Union - just four before 1914:

- Catherine Clarke (1895)

- Owen McCaffrey (1910)

- Rose A. Cosgrave (1911) - all paid for by the Lisnaskea Board of Guardians

- Ellen Murphy, sent by her family in 1899.

This may be because the Lisnaskea guardians may have been reluctant to pay for their local poor deaf children to educated. In 1905, a local Protestant churchman applied for the Lisnaskea Guardians to send young Henry Delmore to the Ulster Institution for the Deaf and Blind.

But one Guardian - named Plunkett - disagreed. He said that the Church should cover the costs, not the Union (although hundreds of deaf children had been sent and paid for by Poor Law Unions in the preceding decades). The Board finally agreed to pay just £5 a year for Henry's fees, and for a limited time.

A few years previously in 1899 Plunkett had raised a similar objection to another deaf child and again suggested the clergyman should pay.

Sources: Freemans Journal, 1 March 1899, p. 8; Fermanagh Herald, 5 August 1905, p. 8.

More information on Lisnaskea Workhouse: https://workhouses.org.uk/Lisnaskea/

|

| Old Lisnaskea workhouse, old entrance block |

|

| Old Lisnaskea workhouse, side of old accommodation block |

|

| Old Lisnaskea workhouse, rear - old accommodation block |

|

| Old Lisnaskea workhouse, rear - old accommodation block |

|

| Old Lisnaskea workhouse, rear of old entrance block |

|

| Old Lisnaskea workhouse, between entrance and accommodation blocks |

![IRISH ECCLESIASTICAL GAZETTE. [SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 28, 1885, p. 990] A CLERGYMAN desires a situation for a deaf mute as parlour maid. She thoroughly understands her duties, and is remarkably intelligent. Trained at Claremont Institution. Apply to Rector, Castlebellingham.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgZo4BudnG5Z-RPreATfhObUY_lYmajrHPJfF62B6Pu8EthRPVVanJMXDthqKkIl87NnmIMqgPkpAjbOvc7sSKCaksqiZXGsw17cXnQYDVGlzKwqDV5_g0v2OGPAOE2cUgZa9ZPpJkg1XKo97DBGTFb-WOp_3J52rnqq5nEf9PuCEF-CbFshPOgnYvG9A/w400-h127/1.png)